A Strategic Model of the Health and Wellbeing System

I have struggled over a number of years to explain my thinking on health and wellbeing strategies in a way that strikes a chord with people. Anyway, this is my latest attempt. This was originally a model to provide a framework for action on mental health as part of a delivery plan for a health and wellbeing strategy. However, with minor tweaks, it applies equally well to health and wellbeing more generally.

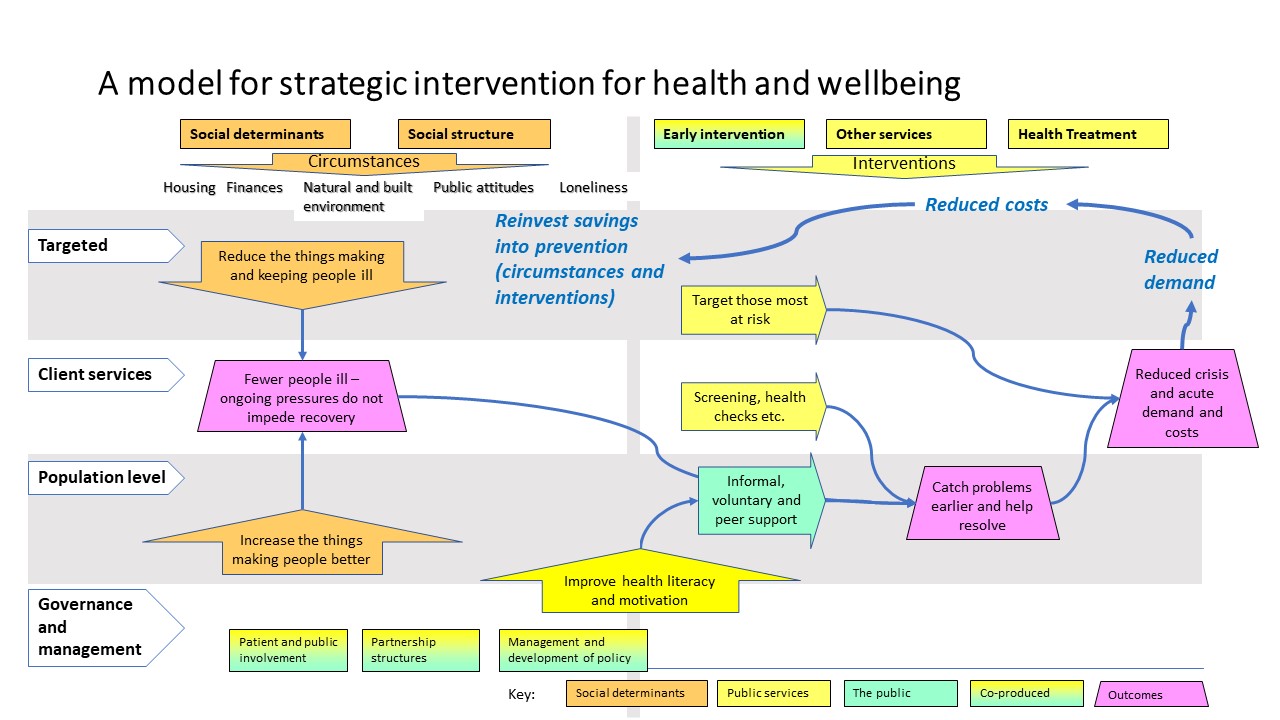

The model shows the social determinants of health (with ‘social structure’ extracted from it, because it is less immediately amenable to change by public services) on the left hand side. In the model, these are the average constant pressures impacting on the health and wellbeing of the population as a whole (although they would only appear at particular times for specific individuals). So, these are the things that influence people to be less happy and healthy (or in some cases, the reverse). They therefore impact on average levels of health and wellbeing but also act as a drag on attempts to improve things. So it is not just a matter of a nice to have, one more thing that can improve health and wellbeing; if nothing is done about them it could undermine other efforts.

On the right hand side are the interventions to make a difference (things that can be stopped and started, rather than the ongoing functioning of the system). So that would include such things as peer support bodies to help people with mental health problems, sports clubs, dieting schemes, health checks, social prescribing, medication, surgery and other procedures. Broadly, as you move further towards the right hand side, this moves from early intervention to treatment for problems.

The other dimension, down the left hand side runs from targeted through to population level interventions, with ‘governance’ tacked on at the bottom. There are other dimensions that could have been used there, but this was something that seemed to work. I am still unsure of precise definitions and whether there is actually a clear distinction between ‘targeted’ (e.g. the troubled families programme) and client services (e.g. claiming benefits).

The first diagram works better because it is simpler. You can clearly see the left and right side, and the flow from prevention and early intervention to reduced demand for acute services, which saves money that can be redirected back into more prevention and early intervention. However, it misses out another important facet of the system – the ongoing dynamics.

The ongoing pressures of the social determinants and the interventions to make a difference do not take place in a vacuum but in a swirling torrent of social relations with leverage and feedback loops that can dramatically amplify or nullify attempts at change. I have added a few of those in the second diagram but this is not really adequate. It means the whole diagram is harder to read. The range of dynamic processes is limited and probably misses out key ones. The way changes to social determinants and interventions can be used to impact on the dynamics, or how the dynamics can be used to enhance the interventions is not clear. But it at least gives a rough idea of the landscape within which a strategy must operate.

So hopefully another step in being better able to explain how a strategy might be able to impact on the health and wellbeing system